At first glance, opposition to the international recognition of Somaliland appears to rest on a familiar principle: the preservation of Somalia’s territorial integrity. The Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) present their position as a defence of sovereignty and regional stability. In reality, this posture has far less to do with Somalia itself and much more to do with a wider geopolitical struggle unfolding across the Middle East, the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.

That struggle pits two competing regional visions against one another. On one side stand the forces driving political realignment and normalization, embodied most clearly in the Abraham Accords. On the other are states and movements determined to preserve an older ideological order—one defined by rejectionism, rigid interpretations of sovereignty, and resistance to Israel’s integration into the region. Somaliland, an entity that has existed in de facto independence for more than three decades, has unexpectedly found itself at the centre of this contest.

Somalia’s unity, after all, has long been more aspirational than real. Since the collapse of the central state in 1991, successive governments in Mogadishu have struggled to exert authority even within the capital, let alone across the country. Somaliland, by contrast, has built functioning institutions, held multiple competitive elections, and overseen peaceful transfers of power—an achievement that sets it apart in a turbulent neighbourhood. Yet many of the states most vocal in defending Somalia’s “territorial integrity” have shown little sustained commitment to rebuilding a genuinely functional Somali state. Their concern, therefore, appears selective: principled in rhetoric, political in practice.

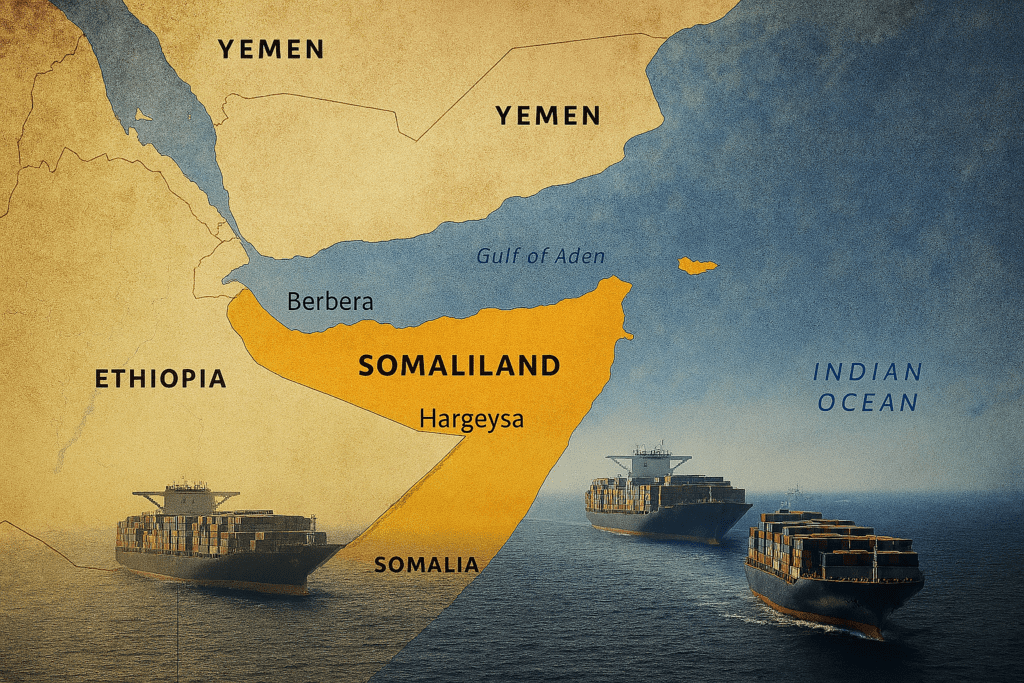

The deeper anxiety lies not in Somalia’s borders but in what a recognised Somaliland could represent. An internationally acknowledged Somaliland would almost certainly align itself with the United Arab Emirates and other Western-leaning partners, reflecting existing economic, security, and port-development ties—most notably at Berbera. From there, cooperation with Israel would become not only conceivable but likely. Another strategically positioned state could thus drift into the expanding orbit of the Abraham Accords, strengthening the normalization bloc along the Red Sea corridor.

In an era when ports, maritime chokepoints and political alignments are increasingly decisive, such a development would carry significant weight. Somaliland sits near the Bab el-Mandeb, through which a substantial share of global trade and energy flows. For states seeking to shape the future architecture of the Red Sea basin, its orientation matters far more than its unresolved legal status.

Saudi Arabia’s uneasy rivalry with the UAE offers a glimpse of the larger struggle. Their involvement in Yemen is often described in terms of security threats and influence, but it also reflects a contest over the region’s future political model. The potential emergence of two Yemeni entities—one hostile to normalization with Israel, the other potentially open to it—would establish a precedent that unsettles those invested in preserving the old ideological order. The battle is thus not merely over territory, but over which alliances and assumptions will define the Middle East in the decades ahead.

Turkey’s posture follows a similar logic. Driven by a blend of neo-Ottoman ambition, ideological positioning, and competition with Gulf powers, Ankara views the Abraham Accords as a rival geopolitical project. A recognised Somaliland near the Bab el-Mandeb would represent not just a new state, but a new outpost of a competing regional order. Opposition to Somaliland’s recognition, in this light, is less about loyalty to Mogadishu than about blocking a shift in the balance of power.

In this context, Somaliland has become both a symbol and a strategic prize. Its case exposes how concepts such as “territorial integrity” are invoked selectively—defended vigorously when they serve broader interests, and quietly ignored when they do not. The real dispute is not about where Somalia’s borders should be drawn, but about who will shape the political, economic, and ideological architecture of the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.

External powers are beginning to tilt the scales. Were the United States to recognize Somaliland, it would instantly alter diplomatic calculations and accelerate regional realignments. Ethiopia, meanwhile, is edging closer to securing long-sought access to the sea, a goal that inevitably enhances Somaliland’s strategic value given their long shared border. China, too, is watching closely. The recent diplomatic activism of its foreign minister, Wang Yi, across Ethiopia and other African states signals Beijing’s determination to protect its maritime routes and economic interests as the regional order evolves.

None of this will be decided in a single dramatic moment. The region’s future is being shaped incrementally, through intersecting pressures, alliances, and rivalries. Yet the direction of travel is becoming clearer. Somaliland’s fate is no longer a narrow legal question confined to Hargeisa and Mogadishu. It is a proxy for a much larger contest—between an old order struggling to hold back normalization and realignment, and a new one intent on redrawing alliances, trade routes, and strategic partnerships.

Whether Somaliland is ultimately recognised or not, its emergence as a strategic magnet underscores a simple truth: the Horn of Africa is no longer a peripheral theatre. It is fast becoming one of the main arenas in which the next regional order will be decided.