Illicit finance between Ethiopia and Eritrea is distorting markets and reviving dangerous habits.

In the borderlands between Ethiopia and Eritrea, economics has begun to misbehave once again. In towns such as Adigrat and Adwa, eyewitnesses describe informal exchange houses trading 15 Ethiopian birr for one Eritrean Nakfa—a rate that appears to defy basic principles of supply and demand. Eritrea imports far more goods from Ethiopia than it exports in return. Even though this commerce occurs informally, given the absence of official trade between the two countries, conventional economic logic would suggest a weak Nakfa relative to the Birr, not an implausibly strong one.

Yet this distortion, local traders say, is no accident. It is the visible tip of a deeper system of illicit finance, contraband trade and political collusion linking entities controlled by the Eritrean regime with front companies and armed networks associated with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) along the porous frontier.

If true, the arrangement amounts to a quiet assault on Ethiopia’s currency markets and economic stability.

How the Arbitrage Works

According to multiple accounts from traders and local residents, the mechanism is deceptively simple. Diaspora-based money-transfer firms—long accused by critics of operating under the tacit influence of Eritrea’s ruling party—offer Ethiopians unusually favorable rates to convert birr into U.S. dollars. These dollars do not pass through transparent or regulated financial systems. Instead, they are retained within offshore or shadow banking networks, commonly routed through hubs such as Turkey, the UAE, Qatar, and, in some cases, Western jurisdictions.

The Eritrean regime then exploits an artificially favorable Birr-to-Nakfa exchange rate—allegedly sustained through collusion with TPLF-aligned power brokers—to recycle birr back into this circuit, effectively exchanging Ethiopian local currency for hard currency sourced from the diaspora. Those dollars can be deployed where they are most valuable: financing external procurement, sustaining regime patronage networks, or—according to growing claims from Ethiopian officials—supporting proxy armed groups operating in and around Ethiopia, including TPLF-linked militias in Tigray and Sudan. In return, TPLF figures involved in illicit gold mining are said to channel gold toward Eritrea’s Bisha mine for further processing and export to Middle Eastern markets. The result is an abnormal Nakfa-Birr exchange relationship that functions as a financial vacuum, steadily extracting resources from Ethiopia.

What looks like a local currency anomaly is, in this telling, a form of cross-border financial warfare.

Addis Ababa Pushes Back

Ethiopia’s authorities appear to have drawn similar conclusion. Speaking in parliament in late October 2025, Prime Minister Abiy urged Eritrea’s government to stop its involvement in illicit black-market financing, human trafficking and arms trading to support militant groups in Ethiopia. More recently, National Bank of Ethiopia published a list of illegal foreign-exchange operators allegedly linked to Eritrean regime interests and froze more than 200 individual accounts suspected of facilitating illicit financial flows. Officials frame the measures as necessary to protect monetary stability and halt contraband financing.

Such steps are unusual in scale and suggest concern that the problem has moved beyond petty smuggling into something more systemic.

A Familiar Pattern

None of this is entirely new. The seeds of the 1998–2000 Ethiopia–Eritrea war—which claimed an estimated 70,000 lives—were sown not only along disputed border lines, but in currency markets and trade corridors. Ethiopia’s reliance at the time on maritime ports controlled by Eritrea, combined with a brief period of shared monetary arrangements, gave Asmara undue leverage over Ethiopia’s import-export trade. Regime-linked trading houses exploited this imbalance, purchasing exportable goods in Birr, selling them abroad for USD and parking the proceeds offshore. Though the conflict is often remembered as a territorial dispute over Badme, it was preceded by deep tensions over exchange-rate manipulation, contraband trade, and Eritrea’s use of informal commerce to extract value from Ethiopia’s far larger economy.

At the time, the government of Meles Zenawi was reluctant to escalate. But the cumulative economic burden—distorted markets, capital flight and the weakening of the birr—eventually forced Addis Ababa’s hand. What followed was catastrophic.

Déjà Vu in Tigray

Today, residents in northern Ethiopia report a renewed outflow of subsidized goods moving northward across the border: fuel, grain, livestock, medicines, coffee, sugar—even bottled water. For Eritrea, some of these goods, like fuel arrive relatively cheaply, as they’re currently subsidized by Ethiopia. For Ethiopians, especially in Tigray and neighboring regions, they are becoming scarcer and more expensive.

The political implications are combustible. As living costs rise and shortages bite, pressure will mount on Ethiopia’s federal government to act—not only against smugglers, but against what it increasingly views as state-sponsored predation by Asmara.

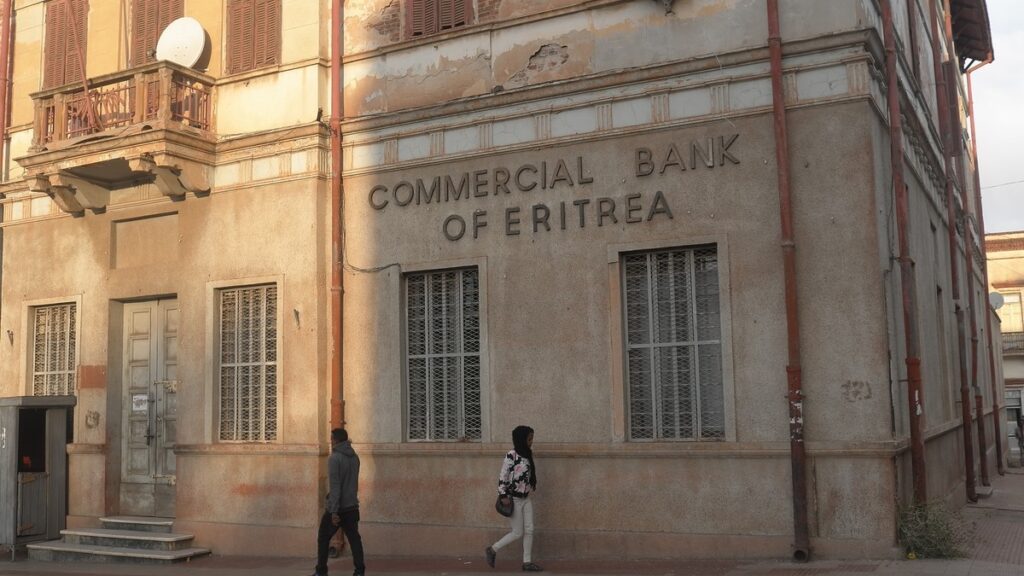

A Small Economy’s Old Strategy

Eritrea’s economy is small, tightly controlled and chronically short of good and services, and foreign exchange. For decades, critics argue, the regime has sought survival through extraction rather than production—leveraging diaspora remittances, informal finance and asymmetric access to Ethiopia’s markets to compensate for its own structural weaknesses.

Such strategies may be rational for a besieged regime. But they are destabilizing for its neighbors.

The Risk Ahead

If Addis Ababa concludes that financial countermeasures are insufficient, history offers a grim precedent. Economic conflict along the Ethiopia–Eritrea frontier has a habit of metastasizing into military confrontation. The current moment, marked by fragile post-war arrangements in Tigray and unresolved regional rivalries, is particularly dangerous.

War, once again, would be a tragic repetition—one driven not by ideology or borders alone, but by shadow money, manipulated markets and the corrosive politics of scarcity.

The question, as ever, is not whether such practices are sustainable. It is how long Ethiopia is willing to tolerate them—and at what cost.