A booming illicit trade, controlled by warlords and foreign investors, is poisoning the land and its people—fueling a cycle of violence

A dangerous and illegal gold rush, orchestrated by former Tigray rebels and TPLF strongmen, is flourishing in the aftermath of Ethiopia’s Tigray region. This illicit trade is poisoning the land, inciting violence, and funneling millions in profits overseas.

Access to the Mato Bula and Da Tambuk gold mines in Tigray is tightly restricted, with sites legally licensed to Canadian company East Africa Metals (EAM) effectively off-limits to unauthorized personnel. This controlled access stands in stark contrast to the documented movement of other traffic, such as vehicles carrying Chinese nationals and local workers, which are granted passage through security checkpoints upon presentation of official-looking documentation, the source of which is not opaque.

For over a year, these very sites have been hubs of illegal mining, part of a sprawling, billion-dollar illicit industry spread throughout the Horn of Africa. The investigation found that the networks controlling these mines are largely operated by former rebels and TPLF warlords who have capitalized on the postwar power vacuum. The profits from this plunder are not rebuilding Tigray but are instead being stored in foreign bank accounts, exacerbating the region’s crisis.

The Mechanics of a Illicit Boom

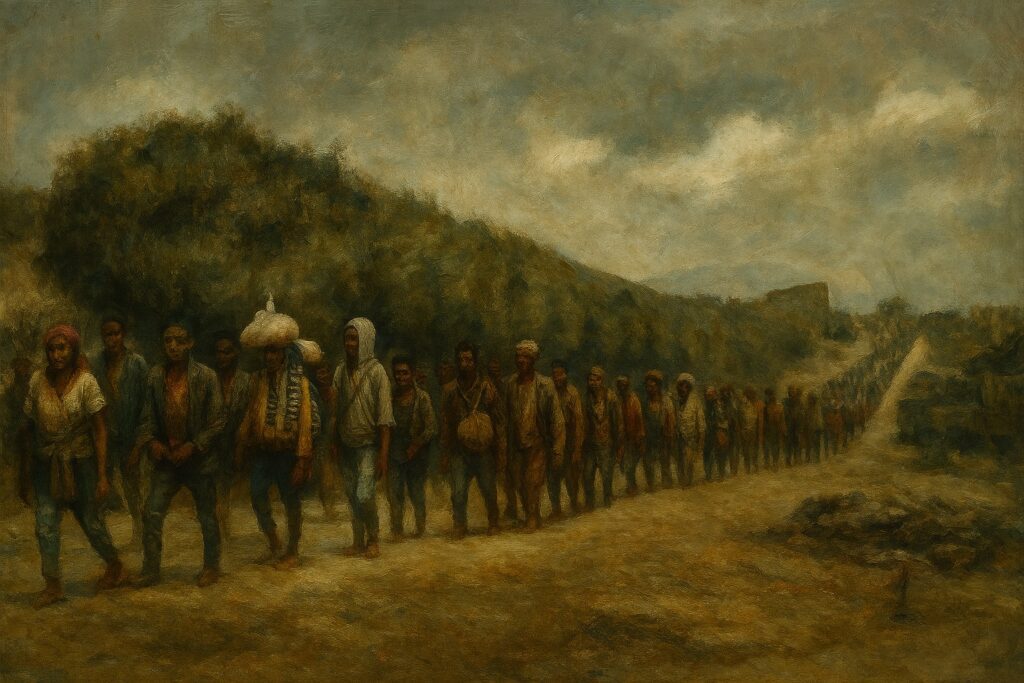

The war between Ethiopia’s federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) shattered the region’s institutions and created a fractured political landscape. In this chaos, former Tigray combatants who refused to disarm and demobilize, as mandated by the Pretoria Peace Agreement seized control of key gold-producing areas. With global gold prices soaring, these armed factions quickly became powerful economic players, now beyond the TPLF’s political wing that once ruled over the region.

These sites could not operate without the approval and involvement of key warlords and the fighters they still command loyalty from. Sources intimately familiar with the trade say, ‘They control the territory, provide security, and facilitate the smuggling networks.’

Dozens of miners, officials, and experts, as well as analysis of satellite imagery and leaked documents, points to a sophisticated system. Foreign investors, often Chinese, provide the heavy machinery and capital. The former rebels provide the muscle, control, and access. The result has been the transformation of artisanal digging sites into large-scale quarries that use toxic chemicals and heavy machinery in violation of Ethiopian law.

At the heart of this system are sites like Mato Bula and Da Tambuk. Publicly, EAM and its China-registered partner, Tibet Huayu, are developing these into legal, industrial mines. A recent report by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, indicates satellite imagery analyzed by researchers shows clear signs of excavation and heavy equipment at the sites throughout 2024, long before any official operational status.

According, Chinese miners employed by companies linked to EAM’s partners have been working alongside former fighters at these sites for over a year. EAM has categorically denied any involvement in or financing of illegal activities, stating it does not engage with military or paramilitary groups.

The Human and Environmental Cost

The toll of this unregulated industry is being paid by the people of Tigray and their environment. To extract gold, miners use mercury and cyanide—highly toxic substances that are handled with no safety protocols. The runoff contaminates soil and water sources.

In villages downstream from mining operations, residents report a surge in health problems. One miner displayed severe welts on her hands, while a woman living near a mine claimed two children in her community died from illnesses she believes were caused by cyanide poisoning. “Without these chemicals, we don’t earn enough,” she said. “But they are also killing us.”

For the thousands of destitute locals who turn to mining for survival, the profits are meager. After the foreign investors and local commanders take their cut, the miners are left with just enough to scrape by, trapped in a dangerous and exploitative system.

The China Connection and Political Power Plays

The flow of capital into these operations is complex, but a key figure emerges: businessman Jingbin Wang. He is the chairman of EAM’s board and holds leadership roles in several Chinese mining and exploration companies that have financial ties to EAM’s projects. His position as chief geologist for a major Chinese mining giant and his roles in Chinese government agencies on critical minerals highlight the strategic interests at play.

The immense profits at stake have triggered a political struggle for control. In June 2024, Tigray’s new interim president, Tadesse Werede, launched a task force to seize mining assets and pause operations, a move officially aimed at curbing the illicit economy but also seen as an attempt to consolidate power over the lucrative trade. But the effort can only be described as hapless, as President Tadesse wields limited power and is mutually distrusted by TPLF generals and the federal government in Addis Ababa. His administrations capacity to reign-in the wrong doers is highly questionable.

This has caused shifts on the ground. While a colonel loyal to the new president now controls Mato Bula and Da Tambuk, sources indicate that the Chinese miners have temporarily left, and equipment has changed hands. The fundamental dynamics, however, remain unchanged.

“The gold economy is fuelling conflict and empowering armed actors in Ethiopia,” said Ahmed Soliman, a senior research fellow at Chatham House. “We should have seen these resources being used to rebuild the region. Instead, they are being misappropriated.” This resource curse problem continues to harm the African continent at large. The continent so rich with minerals is perpetually being exploited by warlords tied to exploitative international networks, often backed by powerful players and even states.

Federal Government Intervention

As the sovereign authority, the Ethiopian government has the legal right and responsibility to manage the country’s natural resources. In a move to assert control over the chaotic and illicit trade, the federal government has enforced a centralization policy. Ethiopian law mandates that all gold, outside of that handled by licensed exporters, must be sold to the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), the only body legally sanctioned to export gold internationally.

This intervention has significantly altered the supply chain. An internal report from the Federal Ministry of Mines revealed a staggering fact: the NBE purchased over 18,000 kilograms of gold from artisanal miners in a single year—nearly 30 times the region’s projected legal output. These funds could go a long way in instituting genuine re-integration of former combatants but also improve the livelihoods of millions impacted by conflict. Government officials Abren spoke to say ,’channeling this trade through centrally controlled legal routes is the only realistic way of insuring transparency and benefit to society. But in the absence of a trusted regulatory body and procedural verification processes, this could be yet another scheme ripe for corruption and resource embezzlement.

The China Connection and Ongoing Instability

The flow of capital into these illegal operations is complex, but a key figure emerges: businessman Jingbin Wang. He is the chairman of EAM’s board and holds leadership roles in several Chinese mining and exploration companies that have financial ties to EAM’s projects. His position as chief geologist for a major Chinese mining giant and his roles in Chinese government agencies on critical minerals highlight the strategic interests at play.

The immense profits at stake have triggered a political struggle for control within Tigray. In June 2024, the regional interim president, Tadesse Werede, launched a task force to seize mining assets and pause operations, a move officially aimed at curbing the illicit economy but also seen as an attempt to consolidate power over the lucrative trade.

This has caused shifts on the ground. While a colonel loyal to the new president now controls Mato Bula and Da Tambuk, sources indicate that the Chinese miners have temporarily left, and equipment has changed hands. The fundamental dynamics, however, remain unchanged.

“The gold economy is fuelling conflict and empowering armed actors in Ethiopia,” said Ahmed Soliman, a senior research fellow at Chatham House. “We should have seen these resources being used to rebuild the region. Instead, they are being misappropriated.”

The illicit gold rush has left a deep scar on Tigray. The proliferation of armed non-state factions whose profiteering continues to fuel instability is enriching a powerful few at the expense of a suffering population.