On February 10, 2026, Reuters published what it described as an investigative report alleging that Ethiopia is hosting a training camp for Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The report, relying heavily on satellite imagery and anonymous official sources, concluded that clusters of tents and container housing in a remote area constituted evidence of a paramilitary facility.

Yet a closer examination of the same evidence raises serious doubts about that conclusion. Far from strengthening the claim, the imagery, logistics, and numerical assertions cited by Reuters expose internal inconsistencies and methodological gaps that substantially weaken the allegation. What emerges instead is a far more prosaic — and well-documented — explanation: the site in question bears all the hallmarks of a large-scale gold-mining camp under development.

The limits of satellite certainty

Satellite imagery has become a powerful journalistic tool, particularly in conflict reporting. But imagery, by itself, is rarely self-explanatory. Context — geographic, industrial, and temporal — matters as much as resolution.

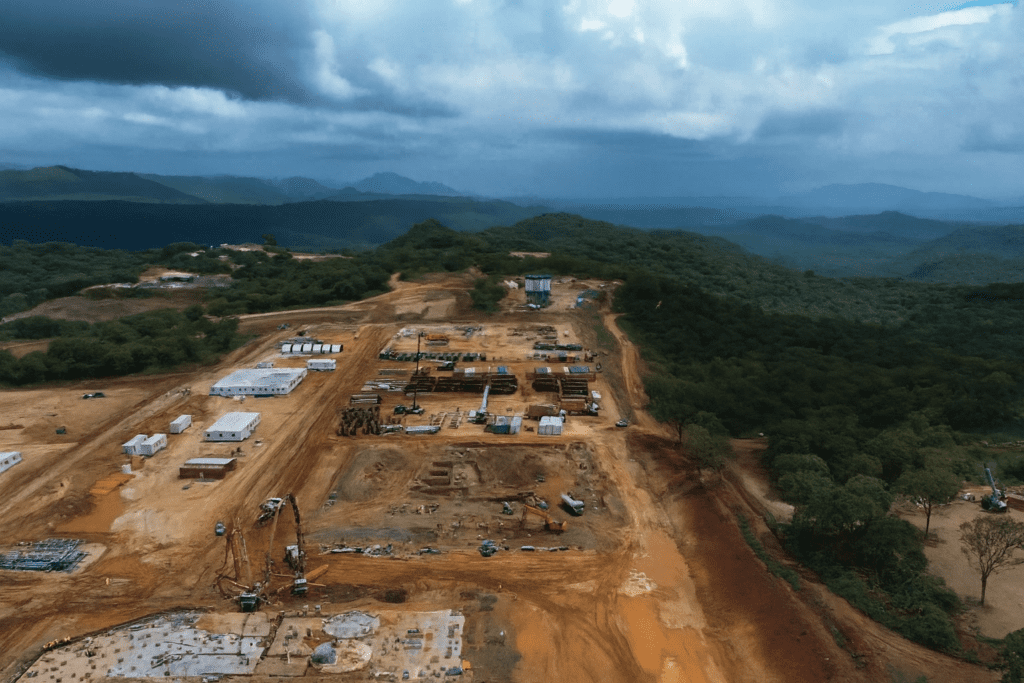

The structures highlighted by Reuters consist primarily of containerized housing arranged in dense, grid-like patterns, connected by dirt access roads and surrounded by areas of recent land clearance. Such configurations are not unique to military installations. In fact, they are commonplace in extractive industries across Africa, especially in gold mining operations located far from established urban infrastructure.

In addition, a Google Earth search of the area in question reveals limestone. Notably, the imagery shows exposed limestone outcrops—an indicator often linked to gold-bearing geological formations and surface mining activity. Such features are routinely visible at mining sites but have no functional relevance to military training infrastructure.

In this case, the resemblance is more than generic. In August of 2025, Ethiopia’s Office of the Prime Minister publicly released video footage documenting the launch of new gold-mining projects in the same region. The structures, layout, and surrounding terrain shown in those official materials closely match the locations now described as a rebel training camp. The continuity of development — rather than abrupt militarization — strongly suggests civilian industrial activity.

If the site were a newly established paramilitary facility, it would be an odd one: conspicuously like previously publicized mining camps yet lacking any visible transition in function.

What a military camp usually looks like — and what this does not

Equally problematic is the physical layout of the site itself. Military training facilities, particularly those intended to host large formations, typically display identifiable features: drill grounds, firing ranges, obstacle courses, segregated command areas, and secured perimeters. Even improvised camps tend to show some evidence of training infrastructure.

None of these features are discernible in the imagery cited by Reuters. There are no open areas consistent with drill or weapons training, no visible ranges or impact zones, and no organizational separation between accommodation and activity areas. Instead, the site appears dominated by uniform housing blocks and earthworks consistent with construction and excavation.

This configuration is entirely consistent with a mining camp in its development phase, where housing and logistics are prioritized before full production begins. It is far less consistent with a facility designed to train thousands of fighters.

Arithmetic as an investigative test

If the visual evidence is ambiguous, the numerical claims made by Reuters are not — and they are internally contradictory.

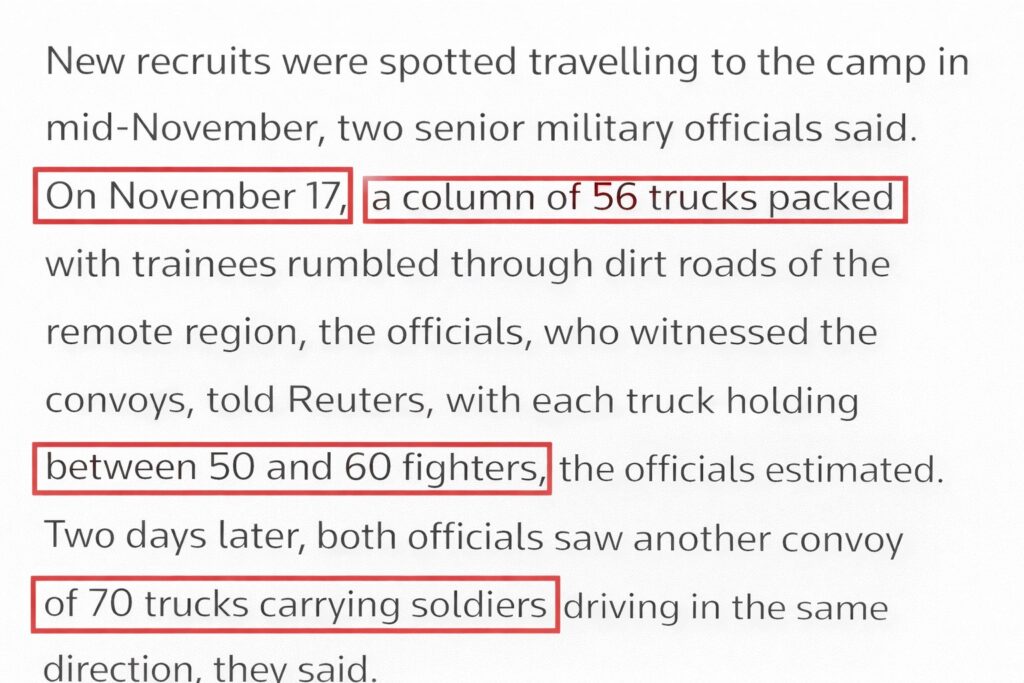

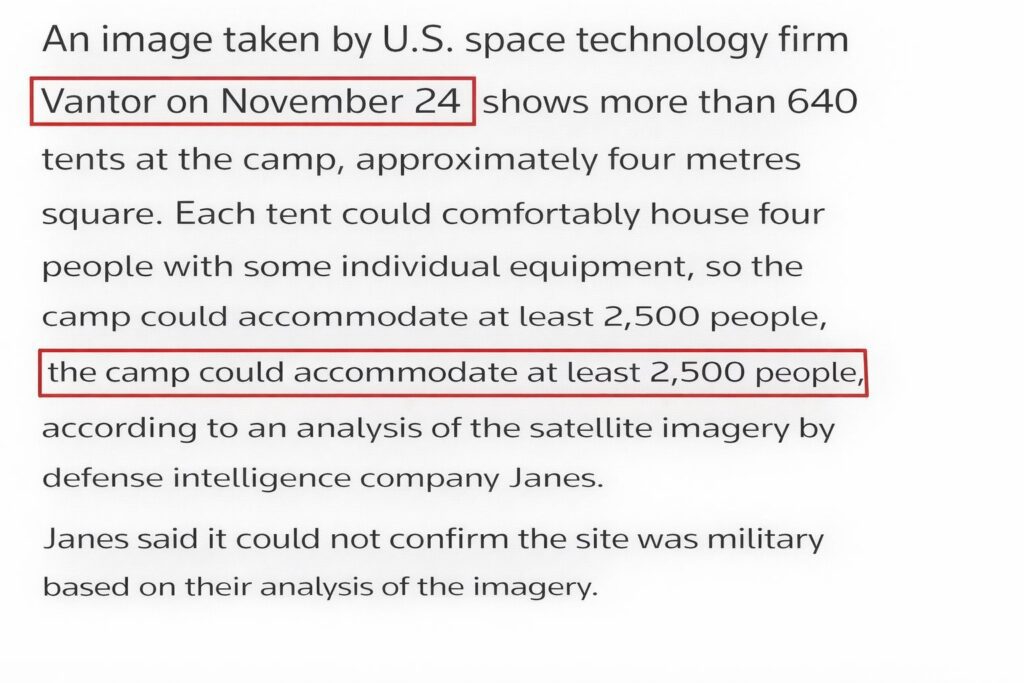

According to the report, the alleged camp had the capacity to house approximately 2,500 people as of 24 November. Yet Reuters also states that five days earlier, 56 trucks arrived carrying an estimated 55 to 60 fighters each, followed two days later by an additional 70 trucks transporting fighters to the same location.

By the agency’s own calculations, this implies the arrival of more than 6,900 fighters within a 48-hour period — nearly three times the stated accommodation capacity. The report offers no explanation for where the surplus personnel were housed, whether they were redeployed elsewhere, or how such a logistical bottleneck was resolved.

This is not a minor discrepancy. In investigative reporting, numerical coherence is a basic test of plausibility. When a claim fails that test, confidence in its broader conclusions erodes rapidly.

The missing expertise

There is also a notable absence in Reuters’ sourcing. While the report cites numerous intelligence and government officials, it appears to have consulted no geologists, mining engineers, or extractive-industry specialists — despite relying on imagery that strongly resembles mining infrastructure.

This omission matters. The site is widely understood to be linked to the Kumruk gold mining area, a project partially owned by the Ethiopian government and partners Allied Gold Corporation, a Canadian-based firm with extensive global operations. Large mining camps routinely accommodate thousands of workers and contractors, often in containerized housing identical to that seen in the imagery. Heavy transport trucks, excavators, and rapid site expansion are standard features, not anomalies.

To interpret such a site exclusively through a military lens, without engaging industry expertise, risks confirmation bias — seeing what one expects to see.

Amplification without resolution

The imagery at the center of Reuters’ report did not surface for the first time this week. It circulated on social media weeks earlier, accompanied by similar claims, which were challenged by analysts who identified the site as a mining camp. Those objections were not substantively addressed before the imagery re-entered the news cycle under the banner of investigative reporting.

This raises an uncomfortable question about amplification. Investigative journalism is meant to resolve uncertainty, not reproduce it with greater authority. When previously disputed claims are revived without new corroborating evidence, skepticism is warranted.

A more likely explanation

Taken together, the evidence points decisively away from the existence of a covert RSF training camp. The imagery aligns with known and publicly acknowledged mining developments. The physical layout lacks any features associated with organized military training. The logistical figures contradict one another. And the reporting omits the very expertise most relevant to interpreting the site.

None of this proves that Ethiopia is uninvolved in the wider Sudan conflict. But it does suggest that, in this instance, an extraordinary claim has been built on an ordinary — if politically sensitive — industrial reality.

Satellite images can illuminate, but they can also mislead. Without context, arithmetic discipline, and appropriate expertise, even high-resolution imagery risks becoming a Rorschach test — revealing more about the assumptions of the observer than about the ground truth below.

Given the accumulation of analytical errors and the relative ease with which the report’s central claims can be challenged, it is difficult to regard this episode as a mere lapse in judgment. At best, it reflects a troubling failure of due diligence, at worst, a reckless disregard for evidentiary standards. This goes beyond poor journalism. In a region already strained by conflict, such reporting risks inflaming tensions and distorting policy debates. The question now is whether Reuters will subject its own work to the same scrutiny it demands of others—and consider correcting or retracting a story whose foundations appear so fragile.