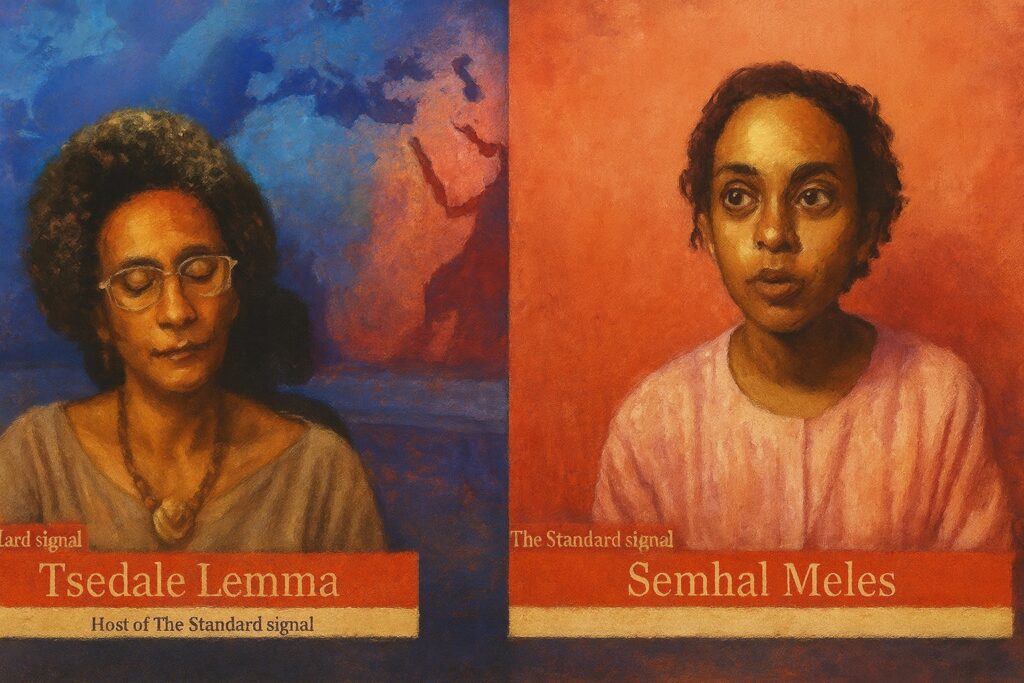

In the inaugural episode of The Standard Signal, host Tsedale Lemma and guest Semhal Meles Zenawi dive into what they call the “manufactured inevitability” of another conflict in Ethiopia—five years after the so called “Tigray war” erupted and three years after the Pretoria Agreement. Their conversation frames the Afar regional government’s November 5 allegation of “Tigrayan shelling” as part of a familiar narrative escalation, one that they argue suspiciously echoes the drumbeats of late 2020.

Convenient Narrative

Semhal argues that a renewed talk of war in Tigray is being “constructed” through rising rhetoric, citing cross-border blame games and militarization of language. But the notion that the federal government “manufactured” the previous conflict as a preplanned scheme to hollow out the region stretches plausibility. The war was set off when the TPLF attacked army bases of Ethiopia’s Northern Command on 3 November 2020, triggering a rapid, chaotic escalation that quickly spilled beyond Tigray into Amhara and Afar over the next two years. In fact, most of the fighting occurred outside of the Tigray region, in Amhara and Afar. And no, there is no covert blueprint tucked away in a file marked “Operation: Make Tigray Collapse.”

This narrative also glosses over the reality that many of Tigray’s service gaps long predated the conflict, shaped by national economic challenges touching all regions. Gold smuggling, property disputes, and institutional decay were symptoms of TPLF’s increasingly predatory nature—not evidence of a federal master plan to engineer regional implosion.

The Neoliberal Bogeyman Returns

Semhal frames Ethiopia’s ongoing economic reforms as “Structural Adjustment 2.0,” packaged as a cynical project to dismantle the state. The satire writes itself: if privatization alone could manufacture a civil war, the entire planet would currently be on fire.

The government’s stated objective—stimulating growth, strengthening industries, and reducing macroeconomic fragility—may be debated, critiqued, even opposed. But to portray these reforms as a trojan horse designed to weaken institutions for the purpose of waging “Genocidal war” is a leap that would make even the IMF blush.

The political crisis in Tigray region is not a deliberate handiwork of a shadowy elites, foreign extractive interests, or their neoliberal economic overlords whose combined project is, apparently, the orchestration of yet another war.

Elections, Preconditions, and Reality

Her insistence that “there is no way out without demanding elections” resonates widely. Yet she sidesteps the unresolved questions: How does one organize credible elections amid fragmented authority, administrative erosion, and an armed faction that reserves the right to reject any result it dislikes?

Demanding elections without acknowledging these preconditions is political wishful thinking—democracy by decree.

Afar, Borders, and the Myth of a ‘Greater Afar’ Plot

In their discussion of Afar, federal actions are cast as part of another grand strategy—this time to empower a “Greater Afar” project. But Afar’s border tensions have long stemmed from local dynamics, historical grievances, and recent escalations driven by political actors in Tigray itself. There is no evidence of a federal blueprint for territorial engineering. Afar communities find themselves in the cross heirs of TPLF militants. They are not beneficiaries of a clandestine expansionist agenda in Addis Ababa.

Sea Access, Sovereignty, and the Temptation to Over-Dramatize

Semhal’s skepticism toward Ethiopia’s quest for port diversification reduces a decades-long strategic imperative into a domestic political diversion. Yet Ethiopia’s dependence on a single corridor is a textbook national vulnerability. The government’s pursuit of alternative access—including naval development—predates current political pressures. As the Prime Minister famously quipped: “We’ve been building a navy for years; were you expecting us to swim?”

Sea access, then, is not a distraction but a structural necessity for a landlocked economy navigating a volatile Red Sea region.

Proxy Games or Political Convenience?

Semhal’s framing of Ethiopia as a pawn of Gulf powers overstates external influence and understates Ethiopian agency. Ethiopia’s geopolitical strategies—port diversification, diplomacy, regional integration—are driven by long-term national interests, not by Gulf directives. External actors matter, but Ethiopia is hardly a marionette. In reality the country’s long esteemed diplomatic heritage is much more developed than anything of the gulf states, particularly within Africa.

The Real Message Worth Keeping

Despite its analytical overreach, Semhal’s most compelling point is her rejection of fatalism: “I don’t believe in inevitability. Fight for a future where our lives count.” This is perhaps the only point that resonates deeply. Given the forces that have amassed in the horn of Africa, a peaceful, democratic, and demilitarized Tigray is a matter of survival—not optional.

But that future requires moving beyond conspiratorial narratives that portray every federal action as part of a master plan for conflict. It requires full implementation of the Pretoria Agreement: DDR, humanitarian restoration, return of IDPs, and demilitarization—all of which remain obstructed primarily by armed actors within Tigray.

Conclusion

Ethiopia is not the helpless stage of foreign intrigues or domestic puppet masters. It is a resilient nation under extraordinary pressure, trying to avert further war while navigating complex political and economic transitions.

Peace in Tigray—and stability in Ethiopia—depends not on rhetorical battles or mythologies of manufactured inevitability, but on genuine cooperation, constitutional governance, and a decisive break from warlord politics, spearheaded by many affiliated with the TPLF and other so called “liberators”. If political leaders reject zero-sum calculations, prioritize reconciliation, and commit to the hard work of rebuilding institutions, a peaceful future is not only possible—it is within reach.