From tribal militias to diplomatic handshakes, Asmara’s deepening role in Sudan’s civil war reveals a dangerous new chapter for the Horn of Africa.

When Sudanese Prime Minister Kamal Idirs stepped off his plane in Asmara this month, it marked far more than a routine diplomatic visit. For Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, whose government spent much of the past two years quietly arming and training Sudanese factions near their shared border, the meeting symbolized something larger: the normalization of a covert alliance that has been years in the making.

Back in 2024, reports from Sudanese and regional observers warned that Eritrea was becoming a critical actor in the eastern Sudan theater of war. As fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) tore through Al-Jazirah and Sinnar states, new armed movements began to appear along the Eritrean frontier—some allegedly conceived with the quiet blessing of Eritrean intelligence.

Among them was the Eastern Sudan Liberation Forces (ESLF), led by Ibrahim Dunia, a former Sudanese police officer turned insurgent commander. The group’s founding conference was held not in Sudan but inside Eritrea, near the village of Tamrat, between May 10 and 13, 2024. Attended by representatives of multiple Sudanese factions and facilitated under Eritrean protection, the meeting drew around 2,000 fighters, mostly from the Beni Amer and Hababtribes.

Eritrean journalist Jamal Hamad noted at the time that Afwerki’s regime “thrives in an atmosphere of wars and unrest,” seeing any form of democratic or civilian movement in eastern Sudan as a direct threat to its own authoritarian order. By cultivating armed groups along its western border, Asmara positioned itself as both gatekeeper and instigator—a patron of instability cloaked in the language of “border security.”

The logic behind Eritrea’s involvement was both strategic and ideological. With Ethiopia’s internal politics fracturing and its military distracted by fallout from the Tigray war, Asmara viewed Sudan’s chaos as an opportunity to project influence. Afwerki, long a master of cross-border manipulation, aimed to ensure that no power vacuum on his western flank could threaten his tightly controlled state.

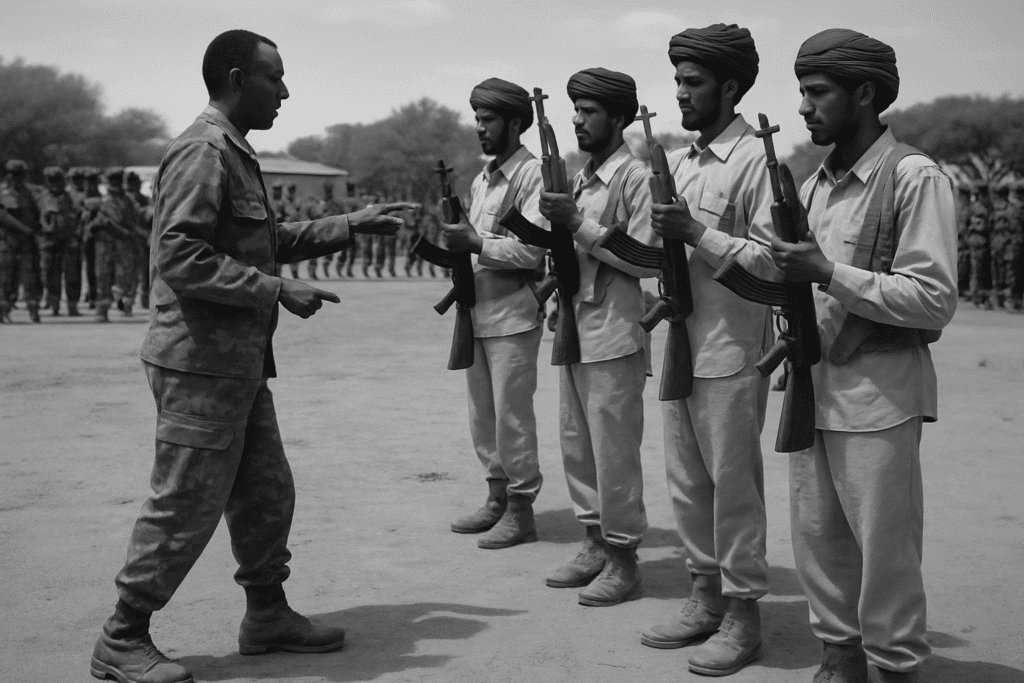

By mid-2024, the Eritrean army had reportedly allocated a 5,000-strong unit to secure the border and maintain oversight of Sudanese factions. The Sawa military camp, Eritrea’s notorious national training center, was also implicated in hosting Sudanese recruits. The expulsion of Sudan’s chargé d’affaires from Asmara that July—after allegations he was spying on these very camps—was a rare glimpse into the scale of Eritrea’s clandestine operations.

Observers warned that the militarization of tribal communities in eastern Sudan risked igniting new ethnic flashpoints reminiscent of Darfur. “The peril,” analyst Khalid Mohamed Taha told Atar, “lies not in civilians arming themselves for defense, but in political actors using these arms to enforce control or settle old scores.”

Fast-forward to late 2025, and what was once covert has become official. The visit of Sudan’s new Prime Minister Kamal Idirs to Asmara cemented a series of defense and intelligence agreements between the two regimes. It follows earlier meetings between Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Afwerki, where both men openly acknowledged Eritrea’s “support” in the war against the RSF.

For the Sudanese Armed Forces, Eritrea offers something indispensable: safe territory, logistical depth, and an escape hatch from isolation. For Asmara, the alliance provides legitimacy—and leverage over both Khartoum and Addis Ababa.

Sudanese aircraft are now reported to be stationed in Eritrea to avoid drone attacks from the UAE-backed RSF, and SAF-affiliated fighters are being trained there with Eritrean assistance. This open partnership underscores how Asmara has moved from deniable proxy operations to formal military cooperation.

The implications stretch far beyond Sudan. Eritrea’s warming ties with Sudan coincide with a marked deterioration in its relations with Ethiopia accusing Asmara of undermining the Pretoria Peace Agreement between the Federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), as well as now providing weapons and training for armed militant groups

By embedding itself within Sudan’s war machinery, Eritrea effectively gains a strategic rear base from which to pressure Ethiopia—a classic move in Afwerki’s decades-long playbook of divide-and-rule across the Horn.

“The Asmara regime has always treated its borders not as barriers, but as instruments,” one regional diplomat told Abren. “Every neighboring war becomes an extension of its own survival strategy”. Since Eritrea does not have the strategic depth to sustain a direct conflict with a much bigger Ethiopia, it must leverage existing conflicts within Ethiopia in hopes of keeping Addis Ababa bogged down.

Given the Al-Fashaga border dispute, simmering tensions over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Ethiopia’s refusal to align with either side in Sudan’s civil war, despite its close relationship with the UAE has caught many by surprise. Meanwhile, the influx of Sudanese refugees into eastern Ethiopia threatens to spill over into cross-border skirmishes, further blurring the line between humanitarian crisis and regional confrontation.

Analysts warn that Asmara’s growing influence could undermine regional peace initiatives, including the IGAD-led peace framework and U.S.-backed “Quad” talks. The more entrenched Eritrea becomes in Sudan’s conflict, the harder it will be to disentangle the war from the Horn’s wider geopolitical rivalries.

For decades, Eritrea has wielded chaos as a form of diplomacy—arming rebels in one neighboring country, hosting rebel movements from another, and trading in the instability it helps create. The transformation of its shadow war in Sudan into a public alliance marks a new phase in that doctrine.

What began as covert tribal patronage has become an official axis of convenience between two embattled regimes—one collapsing, one calcified—bound together by survival and suspicion. As the war in Sudan drags on, the real winner, for now, may be the garrison state next door, whose quiet hand is once again shaping the fate of the Horn.